III - Somewhere Under the Rainbow | 2016-2021 | memymom

ENG | Somewhere Under the Rainbow | 2016-2021

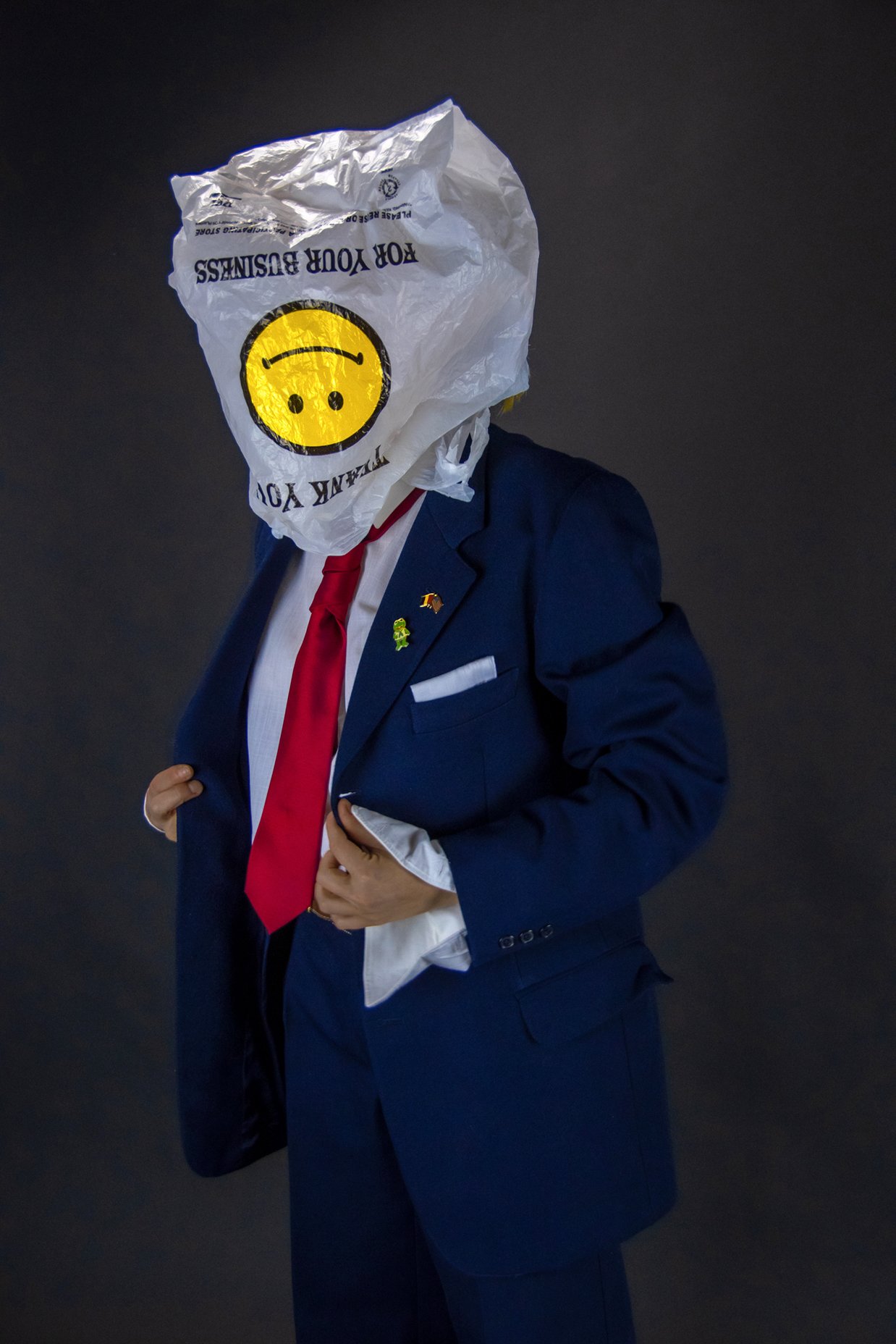

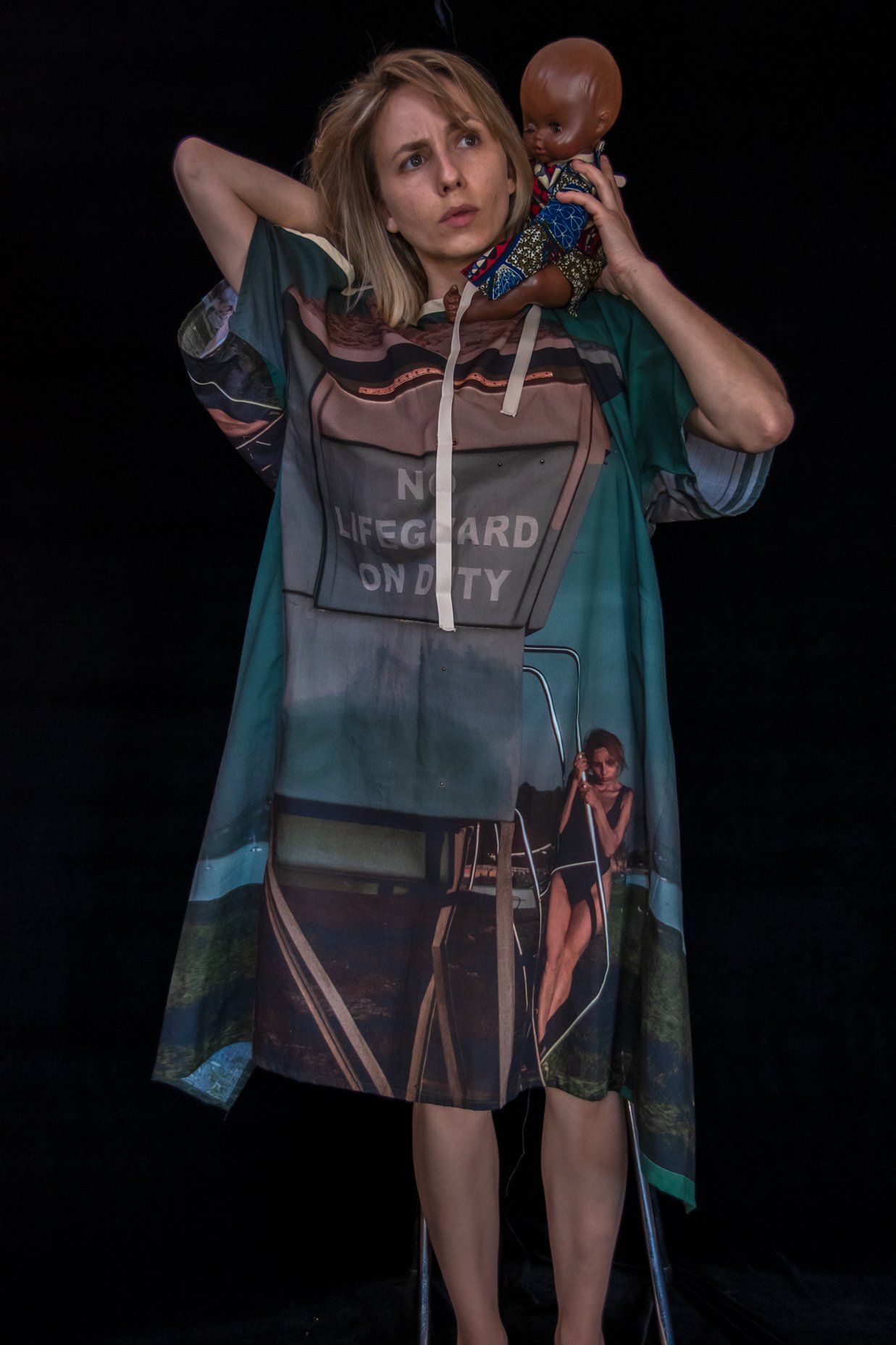

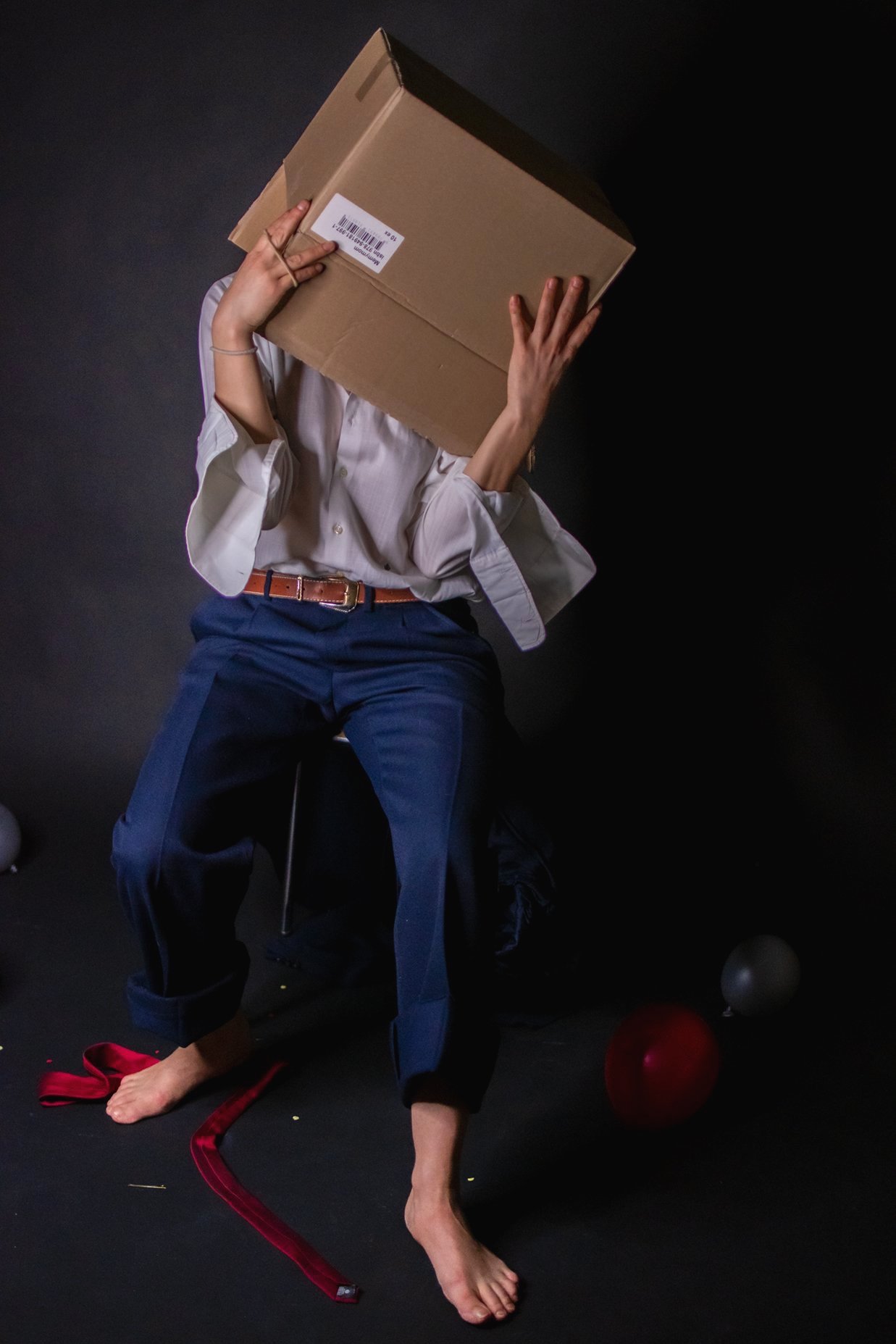

All the images from the third chapter, ‘Somewhere under the Rainbow’ (2016–21) – which is still being developed and are even more multi-layered in terms of their iconography and content, if such a thing were possible. In its most recent work, memymom has added further dimensions and strata of meaning. It moves freely within the space–time of the route it has followed previously by, for instance, creating an image that echoes an earlier one. What’s more, it opens up the time in which the two have been collaborating – there is work here that focuses on Marilène’s memories from the 1960s – or else each of them separately uses props or locations that refer to Marilène’s ‘back story’. Certain images are flashbacks to plots they developed at an earlier stage, such as The Hitcher (2017), which harks back to Hitch in 1996.

Today, memymom rightly and implicitly positions its production between other art forms. Ici Tati (2017) the film language of Jacques Tati; La Vérity (2016) is an overt tribute to Jacques-Louis David’s painting The Death of Marat (1793), while Closing in on David (2017) is set at the house of David Lynch, whom memymom explicitly cites as a general source of inspiration. Referring to or drawing on other art works or practices shows first and foremost that memymom has grown aware of the aesthetic, artistic potential of its own work.

It comes as no surprise that memymom is able to justify every detail in every photograph. It wouldn’t be appropriate and would take us too far from here to analyse and explain every photograph in ‘Somewhere under the Rainbow’ iconographically. Nor is this crucial to the viewer’s reading of the images. But it is typical of how memymom works to construct an image that is then left entirely to the viewer’s personal interpretation.

Although anyone viewing the photographs from the third chapter won’t be able to tell from the visual language alone who is playing the character depicted and who is the photographer (assuming it’s not a third person or an automatic shutter), this strand in the two women’s work includes a variety of self-portraits. In hers, in which Lisa has no hand whatsoever, Marilène makes ample use of masks and old-fashioned tapestries, table-mats, and rugs. Lisa’s self-portraits, by contrast, are primarily determined by the spaces in which she shoots them – the genius loci, the attributes, textures, and structures. The viewer is aware only through extra-artistic information that these are self-portraits. It would be just as possible to read them as images produced by mother and daughter as it is to view them as individual works that are by Marilène alone or Lisa alone. The conclusion that follows from this is an obvious one: Marilène Coolens and Lisa De Boeck unfailingly demonstrate in ‘Somewhere under the Rainbow’ that they are working as two equal partners and that their mother–daughter bond has given way to an equally close and unconditional artistic collaboration between two women. Over the past twenty-eight years, memymom have developed into a professional artists’ collective.

Just like the American artist Cindy Sherman (1954) – known for her countless photographic portraits of herself in ever-changing guises (which Sherman insists are not ‘self-portraits’ as such) – memymom uses the camera to achieve a final photographic result that doesn’t necessarily have a lot to do with the camera or the medium of photography. memymom works intuitively and organically, as Sherman does: ‘My way of working is that I don’t know what I’m trying to say until it’s almost done.’ There is no carefully formulated programme. An idea arises, Coolens and De Boeck research it, pick out the necessary props, and set up their shoot. Ideas mature as they are worked on, within their world and within their work. The story of memymom arose in tempore non suspecto and is utterly authentic.

memymom’s images never resolve into total clarity; there will always be something elusive. That’s what keeps us looking and asking ourselves what is really going on between the artists themselves, between mother and daughter, and between their photographic images and us, their viewers.

NL | Somewhere Under the Rainbow | 2016-2021

Alle beelden van het nog volop in ontwikkeling zijnde derde hoofdstuk, ‘Somewhere under the Rainbow’ (2016-2021), zijn zo mogelijk iconografisch en inhoudelijk nog meer gelaagd. memymom voegt in het jongste werk dimensies en betekenislagen toe. Zo bewegen ze niet alleen vrijelijk in de tijdruimte van het traject dat ze tot dusver hebben doorlopen door bijvoorbeeld een beeld te creëren dat een echo brengt van een eerder gemaakt beeld, ze breken ook de tijd waarin ze hebben samengewerkt, open: er wordt nu gewerkt op herinneringen van Marilène uit de jaren ’60, of er worden door beiden apart rekwisieten of locaties gebruikt die verwijzen naar Marilènes voorgeschiedenis. Bepaalde beelden functioneren als flashbacks naar plots die ze in een eerdere fase al hadden uitgewerkt. Een voorbeeld: ‘The Hitcher’ (2017) gaat door op ‘Hitch’ uit 1996.

Vandaag positioneert memymom haar productie terecht en impliciet tussen andere kunstuitingen. ‘One for Currin’ (2017) roept de schilderkunst van de Amerikaan John Currin op, ‘Ici Tati’ (2017) de filmtaal van Jacques Tati, ‘La Vérity’ (2016) is een openlijke hommage aan Jacques-Louis Davids schilderij ‘La mort de Marat’ (1793) terwijl ‘Closing in on David’ (2017) zich afspeelt bij het huis van David Lynch, die door memymom expliciet als algemene inspiratiebron wordt genoemd. Het verwijzen naar of het betrekken van andere kunstwerken of -praktijken toont in de eerste plaats aan dat memymom zich bewust is geworden van het esthetische, artistieke potentieel van het eigen werk.

Het mag ons niet verbazen maar memymom kan van elke foto elk detail verantwoorden. Het zou ongepast zijn en ons te ver voeren van hier elke foto uit ‘Somewhere under the Rainbow’ iconografisch te analyseren en te duiden. Het is overigens ook niet zo dat dit voor de toeschouwer van cruciaal belang is voor zijn lezing van de beelden. Het is wel typerend voor memymoms manier van werken om een beeld te bouwen dat daarna geheel aan de persoonlijke interpretatie van de toeschouwer wordt overgelaten.

Hoewel wie de foto’s uit het derde hoofdstuk bekijkt niet op basis van de loutere beeldtaal kan opmaken wie het afgebeelde personage speelt en wie de fotografe is (indien er al geen derde hand of een automatische sluiter in het spel zijn), bevat dit luik van het oeuvre van beide vrouwen verschillende zelfportretten. Marilène maakt in haar zelfportretten, waarin Lisa helemaal geen hand heeft gehad, veel gebruik van maskers en ouderwetse tapijtjes, onderleggertjes en vloerkleedjes. Lisa’s zelfportretten zijn dan weer vooral bepaald door de ruimtes waarin haar zelfportretten, inclusief het ‘genius loci’, de attributen, texturen en structuren zijn geschoten. Dat er hier sprake is van zelfportretten komt de kijker alleen maar via extra-artistieke informatie te weten. De zogenoemde zelfbeelden kunnen even zo goed worden gelezen als beelden gemaakt door moeder en dochter, als dat ze effectief kunnen worden gezien als afzonderlijke werken van alleen Marilène of alleen Lisa. De conclusie ligt dan ook voor de hand. In ‘Somewhere under the Rainbow’ tonen Marilène Coolens en Lisa De Boeck feilloos aan dat ze als twee gelijkwaardige partners aan het werk zijn en dat hun moeder-dochterband is vervangen door een al even hechte en onvoorwaardelijke artistieke coöperatie van twee vrouwen. memymom heeft zich in de loop van 28 jaar ontpopt tot een professioneel kunstenaarscollectief.

Precies zoals de Amerikaanse kunstenares Cindy Sherman (1954), die bekend is voor haar talloze fotoportretten van zichzelf in telkens andere gedaanten (Sherman beklemtoont echter dat het geen zelfportretten zijn), gebruikt memymom de camera om een fotografisch eindresultaat te bereiken dat niet noodzakelijkerwijs veel met de camera of met het medium fotografie heeft te maken. memymom gaat intuïtief en organisch te werk, zoals Sherman: ‘My way of working is that I don’t know what I’m trying to say until it’s almost done.’ Er is geen gedetailleerd uitgewerkt programma. Een idee dient zich aan, Coolens en De Boeck doen research, ze kiezen de nodige props bij elkaar en zetten een set op. Ideeën rijpen tijdens de uitwerking ervan, binnen hun wereld en binnen hun oeuvre. Het verhaal van memymom is gegroeid in tempore non suspecto en absoluut authentiek.

Helemaal duidelijk worden de beelden van memymom nooit. Altijd zal er iets zijn dat ontsnapt. Daarom blijven we kijken en blijven we ons afvragen wat er echt aan het gebeuren is tussen de kunstenaars onderling, tussen moeder en dochter en tussen hun fotografische beelden en ons, toeschouwers.

FR | Somewhere Under the Rainbow | 2016-2021

Le troisième chapitre, Somewhere under the Rainbow (2016-2021), est encore en voie d’élaboration, mais toutes ses photos sont encore plus stratifiées, tant dans l’iconographie que dans le contenu. Dans ses dernières œuvres, memymom ajoute des dimensions et des couches de signification. Non seulement les deux artistes se déplacent librement dans l’espace-temps du trajet parcouru jusqu’ici, par exemple en créant une image en écho à une image antérieure, mais elles ne s’enferment pas dans l’époque de leur collaboration : elles travaillent désormais sur des souvenirs de Marilène datant des années 1960, ou l’une et l’autre utilisent des accessoires ou des endroits qui renvoient aux antécédents de Marilène. Certaines photos fonctionnent comme des flashbacks vers des plots élaborés durant une phase antérieure. Un exemple: The Hitcher (2017) enchaîne sur Hitch de 1996.

Aujourd’hui, memymom se positionne implicitement et avec raison entre d’autres expressions artistiques. One for Currin (2017) évoque la peinture de l’Américain John Currin et Ici Tati (2017) le langage cinématographique de Jacques Tati, La Vérity (2016) est un hommage évident au tableau La mort de Marat (1793) de Jacques-Louis David, tandis que Closing in on David (2017) se déroule près de la maison de David Lynch, cité explicitement par memymom comme source d’inspiration globale. En faisant référence à d’autres œuvres ou pratiques artistiques, ou en les impliquant dans sa propre production, memymom affirme avant tout sa prise de conscience du potentiel artistique et esthétique de ses propres œuvres.

Si surprenant que cela puisse paraître, memymom peut justifier chaque détail de chacune de ses photos. Nous livrer à une analyse iconographique approfondie de chaque photo de Somewhere under the Rainbow serait aussi excessif qu’inapproprié, d’autant que, pour le spectateur, ce n’est pas d’une importance cruciale. Mais construire une photo pour la laisser ensuite à l’interprétation personnelle du spectateur est caractéristique de la méthode de travail de memymom.

Bien qu’en examinant les photos du troisième chapitre, il soit impossible de déterminer, sur la base du seul langage visuel, qui joue le personnage représenté et qui est la photographe (si un tiers ou un obturateur automatique n’entrent pas en jeu), ce volet de l’œuvre des deux femmes comprend différents autoportraits. Dans ses autoportraits, auxquels Lisa n’a pas mis la main, Marilène use et abuse des masques, des napperons et des tapis à l’ancienne. Les autoportraits de Lisa, par contre, sont surtout déterminés par les espaces où ils sont photographiés, compte tenu du « genius loci », avec les attributs, textures et structures de l’endroit. Qu’il s’agisse d’autoportraits, le spectateur ne le comprend qu’à la faveur d’informations extra-artistiques, car ils peuvent aussi bien être lus comme des photos prises par la mère et la fille de concert que comme des œuvres distinctes de la seule Marilène ou de la seule Lisa. La conclusion s’impose d’elle-même. Dans Somewhere under the Rainbow, Marilène Coolens et Lisa De Boeck démontrent qu’elles sont deux partenaires équivalentes et que leur lien mère-fille est désormais remplacé par un lien de coopération tout aussi solide et inconditionnel entre deux femmes. En 28 ans, memymom s’est transformé en un collectif d’artistes professionnel.

Comme l’artiste américaine Cindy Sherman (1954), connue pour ses innombrables portraits photographiques d’elle-même sous des aspects toujours différents (Sherman insiste cependant sur le fait qu’il ne s’agit pas d’autoportraits), memymom utilise l’appareil photographique pour obtenir un résultat final qui n’est pas forcément en rapport avec l’appareil photo ou le médium de la photographie. memymom travaille de façon intuitive et organique, comme Sherman : « Ma méthode de travail est que je ne sais pas ce que j’essaie de dire avant que ce soit presque terminé ». Pour Marilène et Lisa, pas de programme complexe préétabli. Une idée leur vient, elles font les recherches nécessaires, choisissent leurs accessoires et plantent le décor. Les idées mûrissent à mesure qu’elles les développent, dans leur monde et dans leur œuvre. L’histoire de memymom, née in tempore non suspecto, est absolument authentique.

Les photos de memymom ne sont jamais parfaitement claires. Il y a toujours quelque chose qui échappe. C’est pourquoi nous continuons à regarder et à nous demander ce qui est vraiment en train de se passer entre les artistes, entre la mère et la fille, et entre leurs images photograhiques et nous, les spectateurs.

Jo Coucke, 2018